Jenkins Best Practices - Practical Continuous Deployment in the Real World

CICD means both

- Continuous Integration and Continuous Delivery

- Continuous Integration and Continuous Deployment

Continuous delivery refers to automatically building each change, and using automation to verify that’s it’s ready for production. It requires a manual step to deploy the changes to the user.

Continuous deployment extends continuous delivery by automatically deploying each change without human intervention.

My team at GoDaddy is responsible for a number of back end services, several web applications, iOS and Android apps. We use continuous deployment for all services and web applications, using Jenkins to automatically verify and deploy each change to production. The mobile apps currently use continuous delivery, due to the manual steps needed to release an application.

Over time, we’ve learned a lot from our efforts, and have put into place several best practices to help ensure success. This post will list some of our best practices, talk about why they are important, and give specific ways we are implementing them.

Store your CICD configuration information in your source control management system

Also called “configuration as code”, you should store CICD configuration information alongside your source code in your source control management system.

Why it’s important: Source control for CICD configuration is important for the same reasons as for your source code:

- You have a history of changes, and can easily revert to a previous version.

- You can ensure quality of changes by having team members review each change prior to integrating.

- Your CICD configuration is not kept on the same server(s) as your CICD system, which means:

- You won’t lose it if the CICD system gets corrupted for some reason.

- Migration to a new CICD cluster should be easy.

How we put it into practice: Jenkins has two types of projects:

- freestyle projects, which are configured via the Jenkins UI

- pipeline projects which are configured via a file named Jenkinsfile in the root of the repo.

We use pipeline projects for all of our CICD pipelines, and any changes to the Jenksinfile in a repo is treated the same as any other change, requiring verification via CICD and approval by two team members.

You should use declarative pipeline

Declarative configuration tells a system what to do, but not how to do it, shifting a lot of complexity to the system. Examples you may be familiar with include:

- Kubernetes, which uses configuration files to indicate how many instances an application needs, leaving the details of creating them to Kubernetes

- SQL, which allows an application to describe data it requires, leaving the database management system to determine the cheapest way to accomplish the task.

Jenkins supports declarative configuration via declarative pipeline.

Why it’s important: Declarative pipeline configurations:

- delegate complexities such as running parallel tasks to the CICD system.

- are easier for both human and machine to read.

- are more portable.

- discourage you from using too many scripts, which leads to simpler pipelines.

- force you to provide a strict stage/step structure for your jobs.

- is where the Jenkins community is putting the most effort, so will benefit more from new features.

How we put it into practice: We have converted most of our Jenkins jobs to declarative pipeline, and all new repos use declarative pipelines. Converting from the previous scripted pipeline format forced us to rethink some of the complexities in our pipelines, leading to simpler Jenkinsfiles. One output of that process was the Github Autostatus plugin, which remove a lot of code from our pipelines. I’ll be writing about the motivation for that plugin, and present its design next week.

Build as much in parallel as possible

Jenkins allows you to build parts of your pipeline in parallel.

Why it’s important: Parallel builds:

- speed up the build/test feedback loop, allowing your developers to be more productive

- speed up deployments, so you can deploy more often

How we put it into practice: In Jenkins declarative pipeline, you might run tests for different environments in parallel, for example:

stage('test') {

steps {

parallel(

test_env1: {

steps to build env1

}, test_env2 {

steps to build env2

}

}

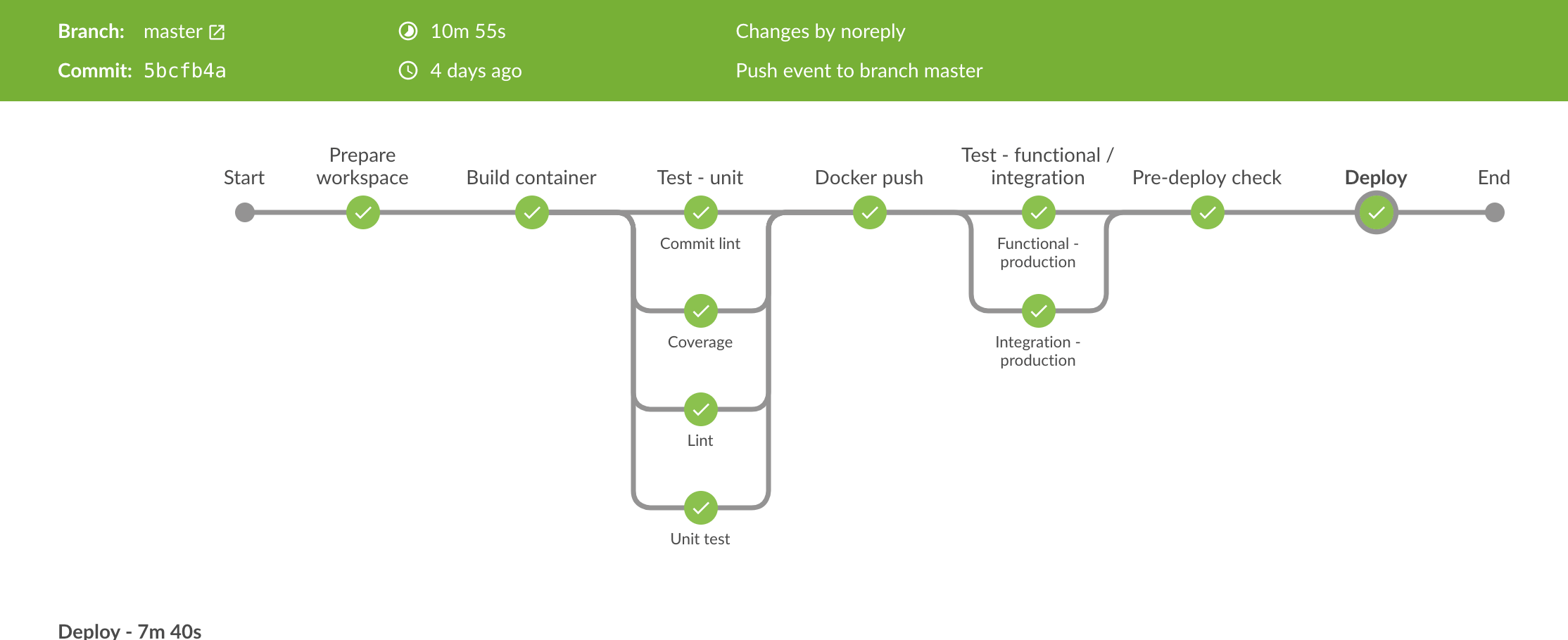

A typical pipeline performs the following stages - failure at any stage fails the job:

- runs unit tests and static analysis in parallel in a Docker container running on the build agent.

- publishes the image

- deploys the image to the container registry

- runs end-to-end and functional tests for development, test and production environments in parallel

- deploys the image to a single instance (canary environment) using Kubernetes, and ensure it can run without issues for a small period of time (typically 2 minutes) while serving production traffic

- deploys the image to our production environment

Pipelines that build multiple artifacts could also build those artifacts in parallel.

Note: When adding parallelization to your jobs, you should always monitor them to make sure it really speeds things up. Things like synchronizing data amongst slaves can in some cases actually cause things to slow down.

You can look at overall build times in Jenkins, or using data from the Github Autostatus plugin

Build and test each change before it’s merged, and don’t allow merges if the pipeline fails

Why it’s important: Building each PR gives the author and reviewers an initial indication of code quality, and blocking merges prevents bad changes from making it into production.

How we put it into practice: We use Jenkins’ Pipeline Multibranch Plugin. This plugin receives notifications of new branches and pull requests and automatically schedules a build for any that have CICD information present.

In addition, we use the Github Autostatus plugin to provide granular status, and do not allow merges unless every status check succeeds. For enabling status checks in github see https://help.github.com/articles/enabling-required-status-checks/.

If your tests take a long time to run, you may be tempted to run only a subset of your tests for PRs to reduce run time, and just run the full suite for master branches. While that’s a valid approach, we try to break up monolithic services up into smaller services, so running the full test suite for PR builds isn’t a problem. The only difference between PR builds and master builds is that we don’t deploy the change to production:

stage('deploy') {

when {

branch 'master'

}

steps {

build job: 'service-deploy', parameters: downstreamGit.parameterValues()

}

}

Pay attention to unit test code coverage and run unit tests as part of your pipeline

Why it’s important: High coverage alone doesn’t guarantee code quality; however, areas of the code where coverage is low or missing is a red flag that the development team isn’t paying enough attention to testing those areas. Surfacing code coverage numbers helps ensure your engineers pay attention to unit testing.

How we put it into practice: We publish code coverage reports in Jenkins as part of our builds. Jenkins provides a trend coverage chart so you can see if coverage is starting to drop.

We aim for 90% line coverage or better, and fail PRs that drop below the coverage, or have Most code coverage packages offer a way to configure build thresholds, but if yours doesn’t Jenkins coverage publishing plugins do (see the Jenkins Cobertura plugin as an example).

Write comprehensive end to end or integration tests, and run them as part of your pipeline

Why it’s important: Your end-to-end tests catch problems not caught in unit tests, and they are what ensure changes don’t break your customer - the more comprehensive they are, the higher your confidence in deploying change.

How we put it into practice:

Early in each project, we have a task to create an end-to-end test to use as a template, then require all stories to include appropriate tests before being closed. It’s important that developers can easily run the tests locally, so part of setting up those tests is to provide any setup or scripts needed for a developer to run and debug tests.

Our method of doing scrum also supports developing tests. We prefer writing stories using the

template “As a

- Open the user management UI

- Add a test user to an existing group

- Log in with that user, and verify the expected page is shown.

A well written story like this, combined with clear acceptance criteria help immensely in creating end-to-end and functional tests.

Finally, when someone finds a bug that wasn’t covered by tests, we write new tests to ensure that problem (or similar problems) will be caught be the CICD pipeline in the future.

Run your CICD tests with the same binaries and environment they will use in production

Why it’s important: You want to rule out the possibility that code will work during your CICD pipeline, but not in production. As an example, if your applications needs a specific port open to work, deploying to a test environment and trying to access it from outside the service will find problems with the port not being opened correctly.

How we put it into practice: Since we use Kubernetes and Docker for our deployments, our CICD pipelines build the docker image, publish it to an artifact repo, deploy a container to the same cloud service that will run the production service, then run tests against the services running in that container.

We also make sure that development environments are able to replicate test runs via the same commands used during the Jenkins pipeline, so developers are able to test their changes locally before submitting their PRs.

Corollary: it probably makes sense to mock or fake dependencies in end-to-end tests

In an ideal world, your end-to-end tests will run in exactly the same environment as your production code; however in practice, mocking or faking dependencies probably makes sense when running tests in your CICD pipeline. There’s a trade-off, because it means your tests may miss bugs if your mocks don’t act 100% like the real services. If you have the proper monitoring and on-call procedures in place, this risk is mitigated.

Why it’s important: Having a flaky CICD pipeline is expensive, since it will slow down your developers if they have to re-run tests that fail occasionally. Having a broken pipeline is even more expensive, as your developers will be completely blocked from merging code. Experience has shown that these real costs outweigh the small but not-zero cost of a bug getting through because the mocks aren’t up to date.

How we put it into practice:

Our application space is made up of a number of smaller services, and we call partner GoDaddy services as well. When we started out, our pipelines called those services as part of their functional and end-to-end tests. However, this caused some flakiness in our pipelines, which slowed engineering velocity considerably.

Eventually we moved toward mocking dependent services, and have had good results. There are no more random failures from problems with dependent services, and we haven’t seen any bugs get through because of mocking. We use a couple of approaches.

Services that are http dependent generally use nock. In cases where that doesn’t work well, it might make sense to create a datastore class to abstract each dependency, then write a parallel fake class that can be called during test. This works particularly well for applications which need to update external data and read back the results. Such mocks are held to the same standards as the rest of the code; the must have full unit tests and undergo rigorous code review whenever they are changed.

A note of caution: you will need to have a way of running tests against the real services at times, because chances are good the mocks won’t behave exactly like the real services. That might mean running manual tests against the real store from time to time, or having a way to configure your tests to run against real services instead of mocks. Also, in the case of nock, you need to update your test responses when the dependent services change.

Monitor your CICD pipelines

Why it’s important:

- Having a broken CICD pipeline can potentially stall your development team. We use 2 week sprints, so not being able to merge code for even a day is a problem.

- Your CICD pipeline might be affected by external dependencies, such as testing services, cloud services, or even the network. You need to know when these occasional failures become significant enough to warrant action.

How we put it into practice: We use several layers of monitoring:

- Our main customer facing build’s health is indicated by lights spread throughout the development area. If the latest master build succeeded, the lights are green. If it failed they are red. We have a small service that pings the Jenkins REST api to determine the current status, but there are also Jenkins plugins that perform the same task (e.g. https://wiki.jenkins.io/display/JENKINS/hue-light+Plugin). (Note that using a plugin will probably require you to modify the build.

- We use the Jenkins Slack plugin to send error notifications to channels monitored by on-call engineers).

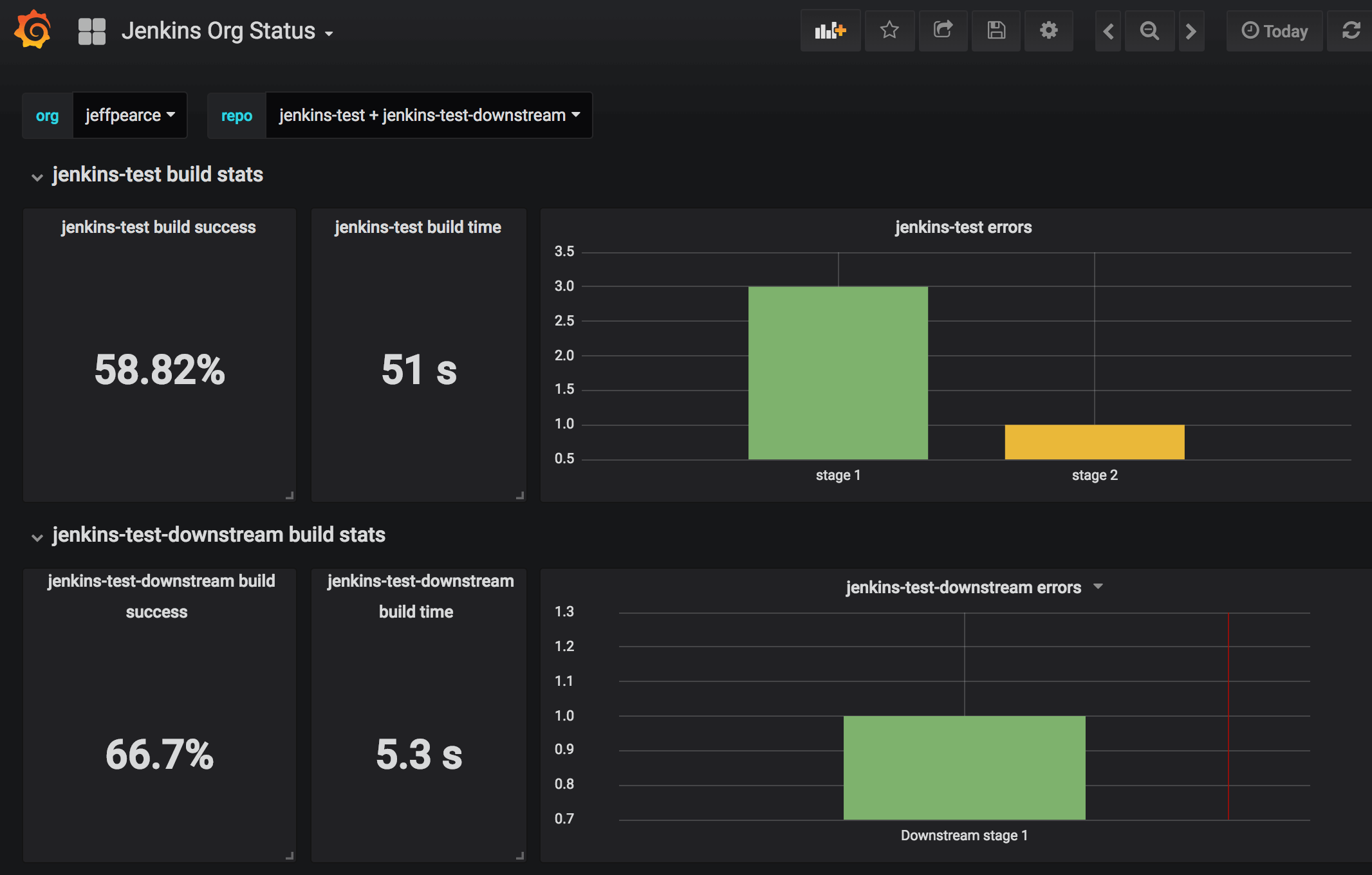

- We use the Github Autostatus Jenkins plugin for monitoring health of our jobs over time. This has allowed us to identify which areas of the build might need improvement. It allows you to build dashboards like the following, which shows build pass rate, average build time, and count of specific stage errors.

This is useful for finding stages which fail too often, and for debugging build inefficiencies.

Have a plan in place for addressing problems in the CICD pipelines

Why it’s important: Problems can and will occur in your pipeline. You may have a test which fails randomly, or have problems talking to a third party service. Sometimes individual build agents can have networks problems which cause builds to fail, and build agents may deteriorate over time.

How we put it into practice: I work with two teams which have different needs, and so have different processes. The client facing team requires its on-call engineer to coordinate investigations and ensure issues are closed. The back end team I work with has several smaller services, and requires each person merging a change to verify that it builds and deploys successfully. If the master build were to fail outside of a PR, the person who first notices it is expected to begin the investigation.

In addition to immediate problems, both teams maintain an infrastructure backlog for lower priority tasks. This is necessary to help balance non-breaking infrastructure improvements with user-facing features and bug fixes. Those backlogs are also addressed separately; the client team requires its on-call engineers to work on infrastructure tasks during their on-call weeks, while the back end team has its scrum teams divide up infrastructure tasks and work on them as part of each sprint.

Have a plan in place for handling bad deployments

Why it’s important: Despite best efforts, bad code might make it into production. Sometimes the infrastructure itself will cause problems. You need to have a plan in place beforehand to address these things.

How we put it into practice: It all starts with monitoring. We obsessively build dashboards that make sure both our system and dependent systems are healthy. We use Sensu to run monitoring checks and notify us via Slack if anything seems unhealthy in the service API. We also use New Relic for finer grained monitoring. Pingdom is another great monitoring tool, as is ELK.

We also maintain on-call channels where partners and GoDaddy customer support can contact us if they find a problem. We make sure each service has adequate logging (and work to improve it over time) so we have data to help diagnose problems.

Anyone merging a risky change should at minimum notify the appropriate on-call channel, and preferably monitor health checks themselves when their code deploys. Note: We are always looking for ways to improve our CICD processes. In the future we plan to roll back automatically if our healthchecks find problems after a deployment.

If there’s a problem that seems to line up with a deployment, we

use Kubernetes’ rollout undo command to revert the pods to the previous image, then

revert the change.

After everything’s fixed, either the on-call engineer or the engineer who deployed the change writes up a post mortem, describing what went wrong, how we found the issue, a timeline, and a list of ways we can prevent the problem. These post-mortems are kept in our Github repository, and undergo rigorous review from the whole team. The focus is always on improving the process, not pointing fingers, so engineers are motivated to be honest in their assessments.

We try to make the lives of our on-call engineers as easy as possible. There’s always a primary and secondary on-call engineer, with an engineer taking the secondary role for a week, followed by a week as primary. This provides some consistency for issues which occur across rotations. Although the on-call engineers are responsible for making sure problems are addressed, they don’t necessarily fix everything themselves. GoDaddy has a strong collaborative culture, and the entire team is ready to pitch in when problems occur.

One final note: I wrote a Jenkins plugin that prevents deployments from happening outside regular working hours or on holidays, as we prefer them to happen when most of the team is available to pitch in if there’s a problem. The Jenkins script for that looks like this:

stage('Pre-deploy check') {

when {

branch 'master'

}

steps {

enforceBuildSchedule()

}

}

That plugin will be available from your Jenkins download center soon.

If you’re using Jenkins, consider getting involved in its open source community

One of the reasons that Jenkins is so successful is the strong open source community. There are plugins that do just about anything, but if you have a need that’s not currently being met, you can always send a PR to an existing plugin, or create a new one if that makes sense. And since the source code for Jenkins is publicly available, you can build and run local versions of any plugins you might be having problems with.

Why it’s important: If you use open source, contributing back to it is part of being a good citizen. But working with the source code also gives you a better understanding of how it works, and building relationships in the community helps you understand how Jenkins is evolving so you can take advantage of newer features.

If you are developing plugins in-house, publishing them to JenkinsCI allows other people to benefit from your work, and gives you a chance to find collaborators. It’s not unusual for the Jenkins team at Cloudbees to enter Jira tickets for the plugins I work on, and I’ve found their input to be invaluable.

How we put it into practice: GoDaddy has a strong open source culture. Internally, we treat all our source code as open source; every engineer has access to the source for every product, and is able to send pull requests to improve the code base. Also, we are strongly encouraged to both use and contribute to public open source projects, and have a process in place for making internal projects available externally. Our Github page contains our open sources projects.

We contribute to Jenkins as part of that culture.

Further reading

- Read about our use of Puppeteer in testing one of our internal applications

- Declarative pipeline documentation

- Build a multibranch Pipeline project

- Parallel stages with Declarative Pipeline 1.2

Note: cover photo courtesy of https://jenkins.io/