The Secret(s) Behind Storing Your Code on the Public Cloud

Software development is tricky. Securely storing credentials and secrets that your software needs access to can often be trickier. We’ve all done it, or at least seen it. You need some credentials in your code to be able to access a remote resource; let’s say a database server. So where do you store that? Well your git repository is private, so you just store it right there! Done deal!

Right?

Except… what if some nefarious individual gets their hands on your code? Now they suddenly have access to that same database, and can wreak havoc on your precious data. Even if your repository is private, there are any number of ways that this can happen. Maybe a team member loses their laptop. Maybe somebody leaks their credentials. Maybe you send a copy of your code to a vendor for them to work on or use it.

And here’s the real kicker: Even if you remove that password from your code, because of the way that git works, it still exists. Anybody who has a copy of that repository suddenly has access to that entire history and every single credential that was ever committed to it. Clearly, that is not an ideal scenario.

Now, this blog post is not about how you should be storing this sensitive data. There are many other posts covering that topic, such as our very own write-up on the GoDaddy-developed kubernetes-external-secrets project. Instead, this post aims to cover what you should do when this potentially grave error has already occurred, and even how to prevent it from happening again in the future!

The Problem

At GoDaddy, we had to face exactly this situation: We wanted to transition our tens of thousands of repositories to GitHub Enterprise Cloud, but had not been historically rigorous about keeping secrets out of git. And with hundreds of teams writing code for over two decades, this was really a bit of an inevitability. So the question then became: How do we not only find and remove all of that potentially sensitive information from all our pre-existing code, but also wipe it out of the history of said code, and prevent any more sensitive data from creeping in there in the future?

The Hunt

Once we had identified our problem, it was time for us to go on the hunt for a solution. Some of the brightest minds in the company came together and compiled a set of several dozen tools to be evaluated for the purpose, and a feature matrix for what we needed. In the end, we settled on the well-known and well-respected tool truffleHog. This option covered the largest swath of our requested features, and on top of that it was open source! Bonus! This meant that we could contribute back to this tool and to the community as we brought this tool up to the level that we ultimately wanted it at for our purposes.

Unfortunately, as with all good stories, there was a problem. Once we settled on this solution, we found that the development for truffleHog had stalled out a bit. It was maintained by a single author at the time, and wasn’t getting the amount of engagement that we hoped for.

The Solution

After much careful consideration, we decided that the best solution for us at the time was going to be to create a hard fork of truffleHog. We would use it and its functionality as our base, and continue to develop it into a tool to meet all of our needs; something we could truly be proud of. At the same time, we would keep this an open source project, to continue contributing back to the community as we had originally intended!

And thus was born tartufo!

Why tartufo, you may be wondering? Well, we wanted a distinct new name while

paying homage to the origin of this project. So we decided that we should stick

with the theme of “truffles”. And according to Wikipedia:

Tartufo (/tɑːrˈtuːfoʊ/, Italian: [tarˈtuːfo]; meaning “truffle”) is an Italian ice cream dessert originating from Pizzo, Calabria.

Source: Wikipedia

It was kismet! I mean, that just sounds (and looks) delicious! Why would we not want that?

The Evolution

Now that we had settled on a path, it was time to begin building this tool into the full-blown solution we were looking for.

The original tool, truffleHog, already contained some great, useful functionality. It could dig through a git repository’s commit history and scan every commit for sensitive data using a combination of regular expressions and Shannon entropy calculation. This meant that we could catch both obvious leaks – things that fit a very specific pattern – and some things that are not so obvious. Things that look more like just a random string of characters, like they might be a machine generated password, key, or something of the sort.

In order for us to use this at scale for enterprise-wide use though, we needed a bit more functionality, and we needed to work on the user friendliness a bit. In the words of the author, Dylan Ayrey:

At the time the tool was meant to be a tool to help [Dylan] with Bug Bounties.

Being a personal-use tool, user friendliness didn’t necessarily need to be top-of-mind. But we were about to encourage several thousand engineers to start adopting this tool across thousands of code repositories. User focus was an absolute must for us. So we changed from a dizzying array of command line options, often mutually exclusive, for selecting the mode of operation, to a set of sub-commands. This gave us the invocation forms of tartufo scan-local-repo for scanning previously cloned git repositories, and tartufo scan-remote-repo, for scanning repositories that the user did not yet have cloned locally.

We also wanted to be able to use this tool to prevent more secrets from getting committed to our code. If it could scan after-the-fact, why not scan before and keep us out of these situations in the first place? This led us to add on the new sub-command tartufo pre-commit, and to add support for using this in the pre-commit invocation framework.

Another essential feature was the ability to create a configuration file, so that we could ensure the exact same options were used every time the tool was run. For this, we decided to utilize the increasingly popular TOML format, and allowed our users to place their configuration directly into the automatically detected tartufo.toml file. Now there was no more need to remember every single option, evern single time you were running the command! Talk about user friendliness.

Finally, we really wanted to be able to fine-tune our false positive exclusions a little better. While truffleHog offered the ability to exclude entire files from scanning, this didn’t really work for us. We needed more fine-grained control over these exclusions, as there may be a single MD5 hash in a comment in a source code file, and we don’t want to have to forsake scanning that entire file just to avoid that one little false positive. Enhancement in this area has seen a lot of work, and it is still continuing to this day. Our new methods of excluding these false positives include (so far):

- Ignoring git submodules

- Allowing regex-based exclusion of high entropy strings

- Exclusion of match signatures

- For this, we generate a stable hash of every single string we find during the scan that is a potential issue. It is generated using the blazing fast BLAKE2 hashing algorithm against the file name and matched string. This means that you can exclude a signature once and any time it pops up in the entire history of the code, it will be ignored.

- File-based exclusion

- This may sound very much like the exclusion feature originally found in truffleHog. And really, it is! But we made one enhancement to it: Previously, the command line flag required you to point to a file which contained all of your exclusion patterns. This could get to be a bit cumbersome, so we enhanced this to instead accept all of the exclusion patterns either on the command line, or directly in the configuration file!

Once we had gotten this work put into place, we realized that it was no use if people didn’t know how to use it, and specifically how to use it to get rid of old secrets that had already been committed to their code, before moving it to the public cloud! So to aid our users, we wrote up a step-by-step guide to run our users through the process of not only finding any secrets that may have gotten scattered through the history of their code, but also how to eliminate them from there with the help of the powerful BFG Repo Cleaner.

The Result

And that brings us to where we are today. Happily scrubbing our history, and actively working to prevent any future problems from occurring!

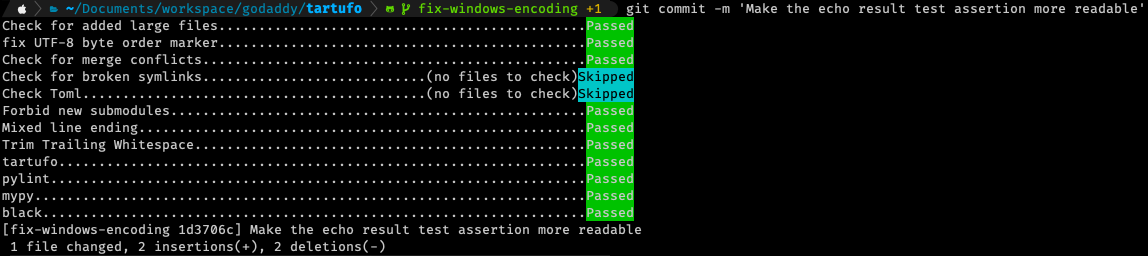

For a quick peek into just how this looks from a user perspective, here is a

real-world example from a commit I made to tartufo itself just this morning:

This is the aforementioned pre-commit framework that we have enabled in

tartufo. As you can see, the tartufo check itself is only one of many checks

that happen automatically on every commit! This has been a huge help to our

developers in actively preventing any new secrets from getting into our code.

And as a bonus, with all of these extra checks happening at the same time, we’re

speeding up a lot of our code reviews by preventing other small, common problems

from occurring.

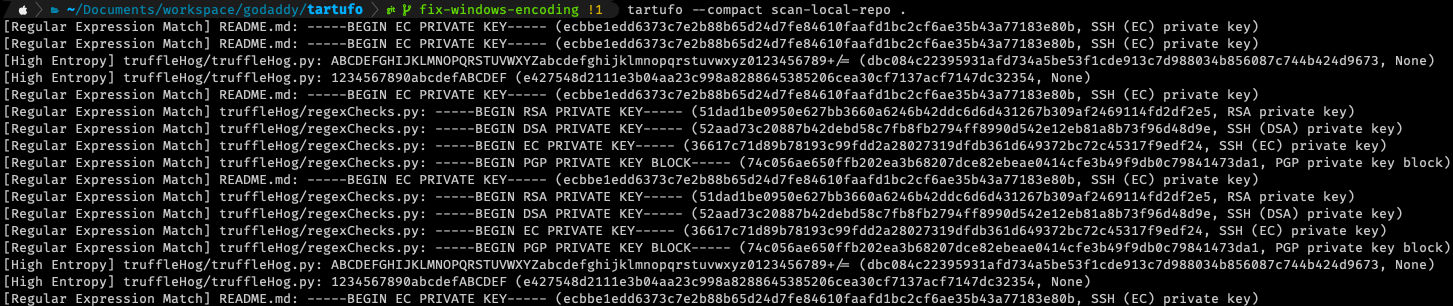

And just for a bit of demonstration, I’ve uncommented some of the exclusions in tartufo’s configuration. Below is an example of what you might see as the result of a scan of a repository with, shall we say, a “robust” history.

You can see that each match gives you a good bit of information about each match – and this is in the compact output mode! Each line is showing you:

- What type of match; Regular expression, or high entropy

- What file the match occurred in

- What was the offending string

- What is the calculated signature for this match

- More detail on match (specifically for regular expressions, this will tell you which regular expression matched)

And if you run this same scan in the default (non-compact) mode, you will get FAR more information. At times, it can be excessively verbose. But all of that output can be useful in understanding the full context of a match in your history.

The Future

Going forward, we know that there is a lot more work that can and must be done to make this tool a true beast. It is not at all without its own set of issues. And, of course, the more users start getting into it, the more issues are found and the more features are requested. In our efforts to continue improving, we are now actively working on Tartufo v3.0! This will primarily include:

- Changing the backend library from GitPython to pygit2. This will solve one

of our users’ primary complaints: Speed. This tool is not fast. And a large

part of that is because, behind the scenes, we’re just issuing

gitcommands in a sub-process and then reading the result. With this change, we will be able to directly understand the git db itself, and work directly with that, removing several layers of abstraction that are currently slowing us down. - A new

scan-foldercommand. If we can scan a repository, why can’t we just scan a folder full of files? Yay for expanded modes of operation! - Live output! Right now, tartufo holds onto all of the results and spews them out to the user as one big lumped together message once its finished its work. This will help solve the frequent user question of, “How do I know it’s actually doing anything?”

- Updated documentation! We have lots of documentation now, but it can always be better. We’re going to be incorporating all user feedback we’ve gotten so far, and working to make the docs as user friendly and helpful as possible.

- A GitHub Action, published to the Marketplace, so that you can run tartufo against every pull request and make sure those pesky secrets aren’t making it into your code.

…and more? Want to contribute to the development of tartufo? It is a free and open source project, so all contributions and contributors are welcome! Check out our contributing docs to see where to get started.

Wrapping Up

Thank you for taking the time to read about our journey! Keep your eyes on this space for future announcements about the development of this tool, and all the things we are doing to ensure we stay as secure as possible in the future.

Want to help us work on these tools and help empower the future of Everyday Entrepreneurs? GoDaddy is always looking for more talented individuals! Check out our careers page to find the role that is perfect for you!