Chasing Runaway Memory Usage in Istio Sidecars

This isn’t one of those blog posts where I brag about the awesome open-source software I’ve worked on or how I’ve oh-so-smartly optimized some code to perform a little better and delight our users. It’s more of a mea culpa, a confession about a simple bug that I sent to production that caused our team some headaches for a few days.

But this story isn’t about the bug itself. It’s about the journey I took to find it.

Happy little services

My team runs several services on a developer platform that uses the service mesh tool Istio. A service mesh is a tool for dynamically orchestrating traffic between a large number of services. It gives us the flexibility to shape and monitor traffic as our developers add or change their services. Our developers love using it too because they’re able to leverage Istio’s powerful routing to deploy canaries and feature-flagged services with minimal effort.

One handy feature of Istio is that it exports Prometheus metrics that help us monitor all the traffic going between any two services in the mesh. It even monitors traffic going from our services to other websites outside the mesh. We can monitor latency and throughput for all our apps without having to deliberately add any instrumentation code. Of course, there’s no such thing as a free lunch. All this monitoring comes at a cost, but generally we think the small overhead of generating and storing these metrics is well worth the extra insights they provide.

We’ve been running Istio for well over a year and the only issues we’ve had were due to operator operator. Our problems have been more to do with our inability to use Istio correctly than with Istio itself. But a few months ago one of our developers deployed a new service on our platform and then things started getting weird.

Their service was just a reverse proxy that helped several newer services communicate with a few legacy services in a consistent way. It was a simple, practical piece of micro-service plumbing that bordered on the mundane. It served thousands of requests per minute all day long and never caused any trouble, until one day we got an alert that our Kubernetes cluster had evicted it from the cluster for using too much memory.

An unfortunate discovery

How could a transparent proxy with almost no state use so much memory that it would get evicted? I was curious, so I did a quick check of the current memory usage of services on the cluster. kubectl top pods showed me several services using modest amounts of memory under 100MB each, but every single replica of this proxy was using over 500MB of memory! Eager to blame somebody else for this unfortunate discovery, I prepared to fire off a message to the development team informing them of their poor memory management and asking them to fix it. But before I passed the buck, I remembered that kubectl top pods also accepts a --containers flag that breaks down memory usage by each individual container within a pod. I inspected the memory usage of each individual container and was surprised to find, that while the containers for the proxy service itself were only using a tiny amount of memory (as expected), the Istio sidecar which records metrics about all the traffic in and out of the pod accounted for the lion’s share of the total memory footprint. This discovery was a little disappointing because now I knew that this problem was definitely my responsibility to fix and I couldn’t play the classic “blame the developers” card to get out of it.

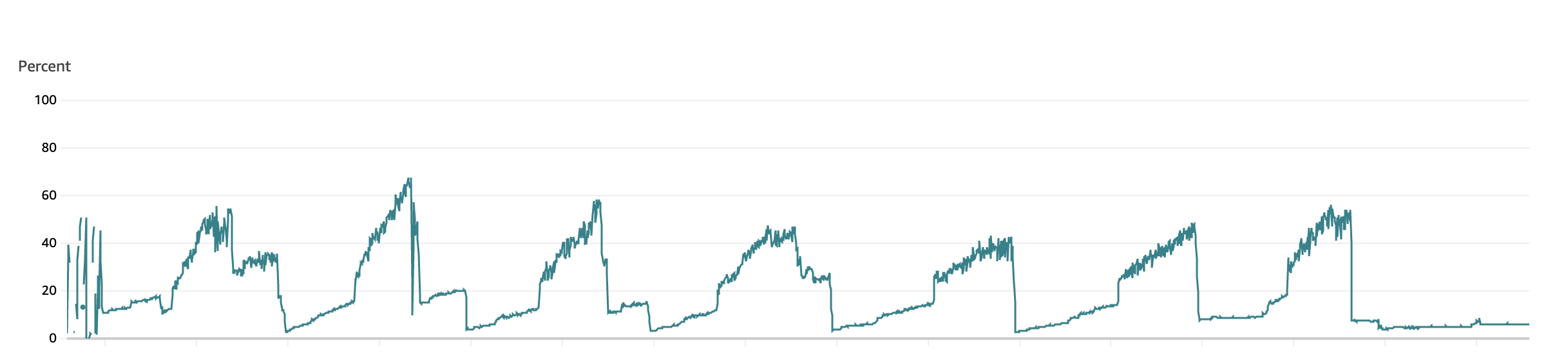

I went to our AWS CloudWatch metrics to see more historical data about the service’s memory usage and was greeted with this frightening pattern that screamed “memory leak”:

Each day, the service’s memory usage would rapidly climb and would only fall when we restarted it each night as a matter of policy, or when it was forcefully restarted earlier than that by a new deployment. In the worst case the service was kicked off the cluster for exceeding its memory limits.

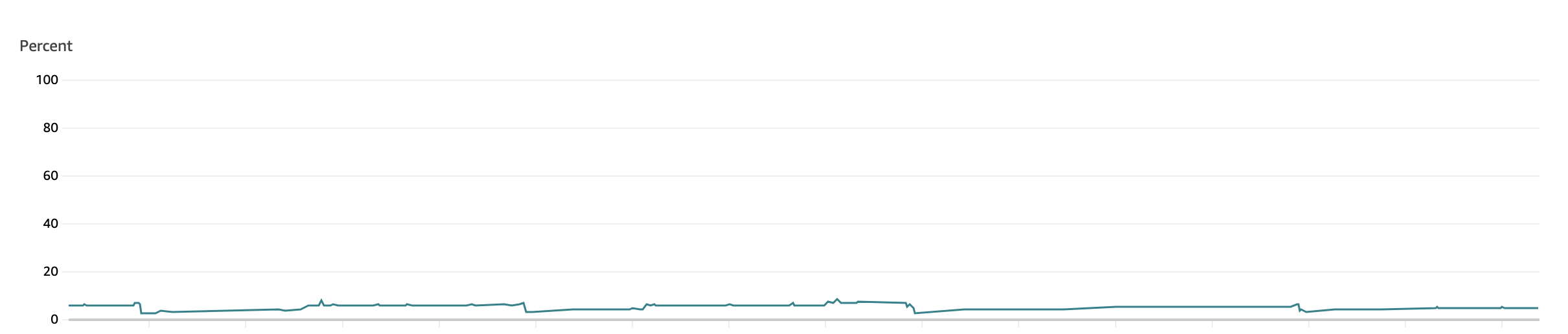

I checked the other services related to this misbehaving proxy, but they all showed remarkably flat lines of memory usage throughout the day, gently ebbing and flowing but not drawing any attention. I checked the misbehaving service in its development and test environments and also found flat lines of memory usage.

So here I had a memory usage pattern that only appeared in production, only affected one service, and covered its own tracks every time it restarted. Debugging this one was going to be tricky. As annoying as this problem was, it wasn’t actively disrupting production so I had the luxury of time to observe the service, poke at its metrics and configuration, and slowly begin to understand the root cause.

Following clues

Knowing that Istio’s sidecar was the one using all the memory was a huge step forward in the debugging process, but also a source of frustration. It’s somewhat easy to scour your own source code for a bug, but it’s a little tougher to find bugs in such a large and foreign codebase. Istio has very clear documentation about the performance and scalability of their sidecar, which claims that at 1000 requests per second the sidecar should only use around 40MB of memory. Googling “Istio memory leak” leads to a barren wasteland of stale GitHub issues full of irrelevant symptoms and snake-oil “fixes”. I literally spent a full sleepless night poring over old Istio docs for clues; it was so baffling to me that this problem could be happening to me without affecting or being reported by anyone else.

As a pure shot in the dark, I tried disabling the Istio sidecar’s scraping of the proxy service’s own exported metrics and noticed that the pod’s rate of increase in memory usage slowed significantly (although it was still growing at a concerning rate). This meant that I was getting closer to the problem; it had something to do with Prometheus.

Knowing that the symptoms were the worst (and thus most obvious) during peak business hours, I waited until the magic time, turned on Prometheus’ scraping, and let the memory usage begin its rocketship-like ascent into oblivion. Then I started manually scraping the metrics and analyzing them to look for clues. One of the most common reasons that Prometheus uses excessive memory is when it has high cardinality, meaning it has to keep track of many unique sets of time-series data at the same time. As I looked through thousands of metrics and labels, I began to notice tons of metrics that the Istio sidecar creates to record request latency and size, and each metric had a different value for the “destination_service” label. These labels had values like “abc.123.myftpupload.com” and I immediately understood the problem.

Revelation

Domains like “abc.123.myftpupload.com” are an artifact of our Managed WordPress and Hosting products that act as a placeholder domain so our customers can manage and preview their sites before they’ve purchased their own domain. I surmised that this proxy service was making requests to those sites, perhaps to generate thumbnails of them or collect some relevant metadata to show the user. But each time one of these requests was made, Istio did its job and recorded lots of metrics about our request to the service. Each user’s request resulted in around 25 new time series being added to the Prometheus database, increasing its memory footprint each time.

Knowing this, my frenzied Googling got a lot more productive. Istio has a specific FAQ about high cardinality caused by the “destination_service” label and provides specific guidance on how to address it. Basically, Istio tries to interpret every “Host” header it sees in requests as the identity of a new service and records it as a separate time series. This behavior is called “host header fallback” and is enabled by default. While it could be useful for some services, it’s definitely a hindrance for a service that talks to hundreds of thousands of unique services throughout the day.

I disabled host header fallback by making a few small edits to our mesh’s Envoy filters and after one final restart of the sidecar to flush its memory, the memory usage went from aggressive daily peaks to this very pleasant and flat level of usage over the next few days.

Looking back

Many developers cringe at the thought of having to solve a bug that seems impossible to reproduce. You see, easy bugs are just that—easy. I run into these often, and usually with the help of an APM trace and a few lines of logs, I know exactly which line of code is responsible and exactly what change I need to make to fix it. Ironically, filling out the “paperwork” (JIRA) and waiting for our CI/CD pipeline to deploy the fix all take longer than fixing the code itself.

But hard bugs…oh, let the hair-pulling begin. After trudging through the five stages of debugging grief, hard bugs are one of those things that will monopolize my brain until I figure it out. I pride myself on deeply understanding the tools I work with, so hard bugs are a loud, nagging voice pointing out that there’s something, somewhere, that I’ve missed.

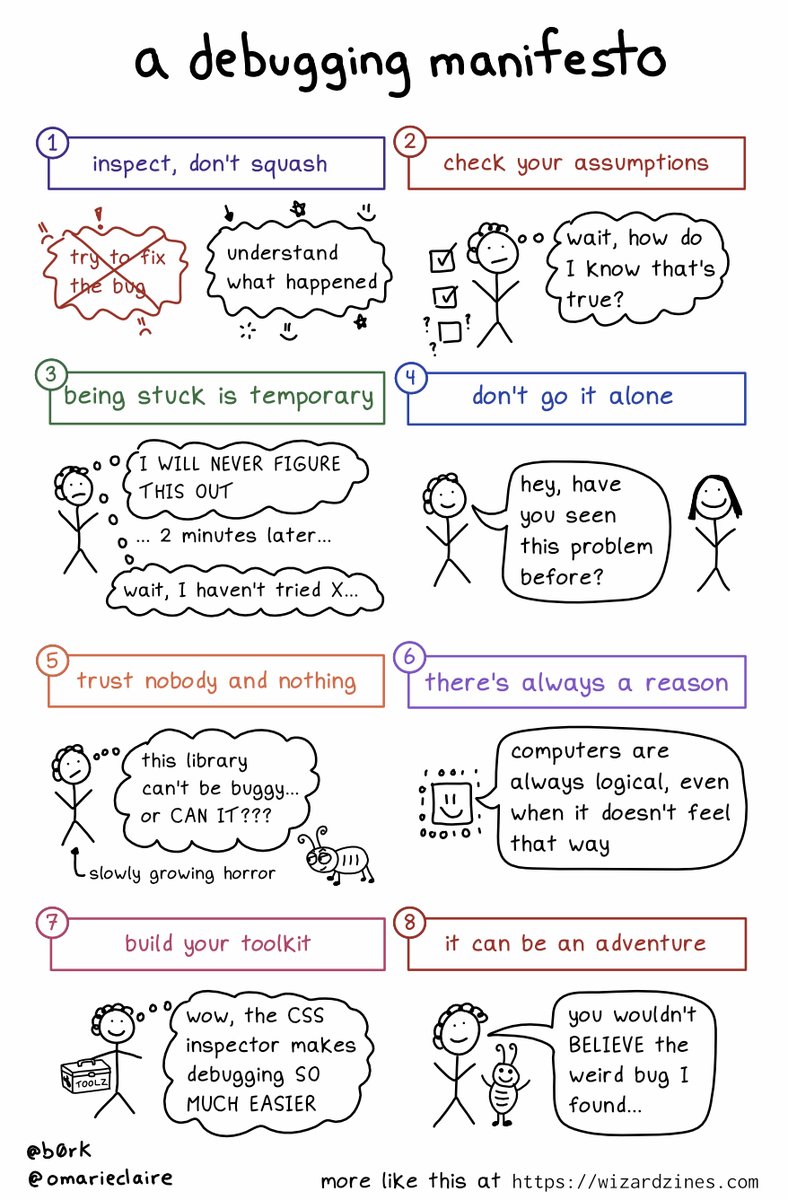

In a remarkable coincidence, just a few hours after I finally figured out and fixed this memory problem with our Istio sidecars, Julia Evans posted this great perspective on debugging, ending with the same realization I just had: Hard bugs aren’t always bad things—sometimes they’re an invitation to go on an adventure.

🔎Julia Evans🔍 on Twitter: “a debugging manifesto pic.twitter.com/3eSOFQj1e1 / Twitter”

Cover Photo Attribution: Photo by unsplash: https://unsplash.com/photos/a4W1kvrMGXs