Building a robust mobile to webview bridge with RxJS and Redux

In this post, we’ll take a look at how our team built a duplex bridge between our mobile and webview code. We use this bridge to send messages between both sides. We’ll dig into how we use RxJS observables to deal with messages from the bridge combined with actions dispatched from our React app.

Introduction

Our team, the GoDaddy Studio team, focuses on building mobile apps that our customers use to create social content and engage with their followers. Over the last few years, people on social media have started using simple mobile-first website builders to publish websites that they link to on their social media profiles. These simple websites are used to show off more content and link to their other social media profiles. This type of website is commonly known as a Link in Bio site.

We felt that a Link in Bio tool would be a great addition to the GoDaddy Studio app since our customers already use Studio to create media posts, loved the experience, and knew all the tools. With this in mind, our plan was to provide the same familiar editing experience for building websites too.

Our GoDaddy Studio app consists of native mobile code targeting iOS and Android. On both versions of the app, the tooling is purpose built to suit each platform. We wanted to provide a familiar editing experience, so we decided to reuse the tools as much as possible. We considered whether we should also render the actual website in native code during an editing session. In the end, we decided against this approach because we worried about duplicating our efforts. It would require us to build a renderer in native code on two platforms and we’d still need the rendering logic for when the website is published in the end. We were also concerned that the three renderers would diverge in their output. In the end, our whole team agreed that we would render the website in a webview while the user edits it. But how do we get our native tools to drive changes in the webview and get the tools to react to those changes?

Bridging between mobile and webview code

This is hardly a new problem. Engineers have been doing this for years. But our requirements were different from most scenarios due to the nature of our app. Our bridge started out quite simple and evolved over time to what we have today. Let’s look at where we started and where we ended up.

Our initial approach

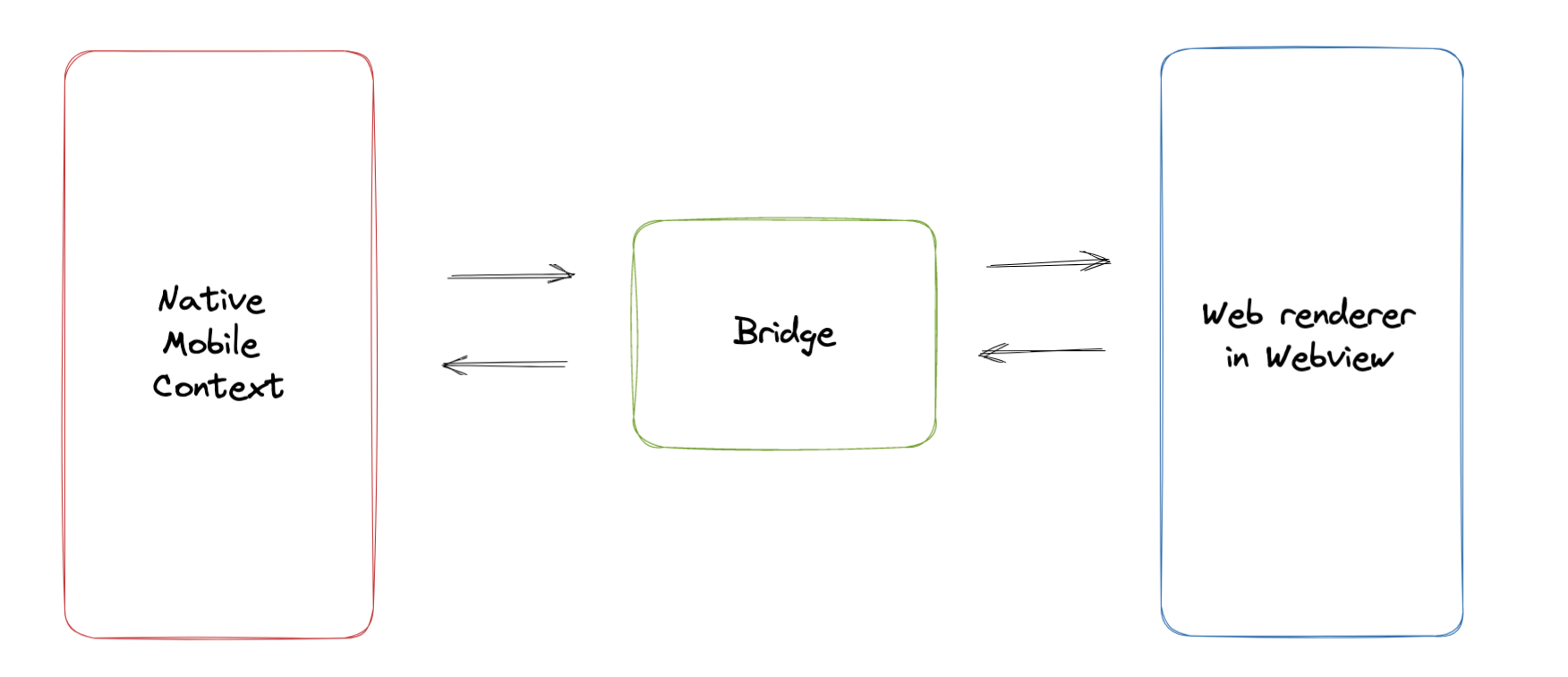

A mobile-webview bridge lets mobile code and webview code communicate via messaging. The mobile code sends messages to the webview code and vice versa.

It’s important to point out that these messages are fire and forget. The mobile code doesn’t wait for a response from the webview code. The webview code doesn’t wait for a response from the mobile code. This is a very important distinction.

We won’t go into the implementation on sending and receiving messages in mobile or web, but it’s important to note that we wanted uniformity in our messaging format. We achieved this by settling on an API based on the well known postMessage API.

The postMessage API is also a fire and forget API. It takes a message as a string and sends it to the other side. That’s exactly what we also settled on, but we added a bit more structure to our messages.

As our postMessage payload, we send serialized JSON in the following format:

{

"type": "some-type",

"payload": {

"some": "payload"

}

}

If you are familiar with Redux, you’ll notice that this format looks like actions. This is intentional. Our webview contains a React and Redux app that represents our user’s website. So it made sense for us to use the same action format for our bridge messages. With this approach, we could dispatch actions from both our mobile code and our webview code. These actions are then available to the same middleware and reducers.

Making it more resilient

As a reminder, our bridge needs to handle messages to support native mobile tooling to make changes in our renderer. This includes rapid fire scenarios, for example, scrubbing through colors in a color wheel. We also ended up with mission-critical messaging that we wanted to handle reliably, for example, saving and restoring an editing session.

As an aside, we ended up with non-rendering code in our webview to move quicker on our project. We opted to keep the tooling and mobile context ignorant of the actual state inside the webview. We had a strict contract between the native context and webview context. That’s why we ended up with the webview being heavily involved with concerns like publishing, session storage, and syncing. The webview code had access to the current state of the website, so we decided it was best positioned to handle these concerns.

So we were in a position where we had the basics of our bridge in place and had tooling sending us all sorts of interesting messages. But how could we ensure that we could handle messages reliably? Well, we added RxJS observables. RxJS works well in scenarios where you have a stream of events that you want to process. And that’s exactly what we had. Plus, I kinda like RxJS… Guilty. Instead of adopting a library like redux-observable, we decided to build our own simple middleware:

import { Subject } from 'rxjs'

import { Action, State } from '../../types'

import root$ from './root$'

export default function observableMiddleware({

dispatch,

getState,

}: {

dispatch: (msg: Action) => void

getState: () => State

}) {

const state$ = new Subject<{ state: State; action: Action }>()

root$(state$).subscribe((action: Action) => dispatch(action))

return (next: any) => (action: Action) => {

const returnVal = next(action)

state$.next({ state: getState(), action })

return returnVal

}

}

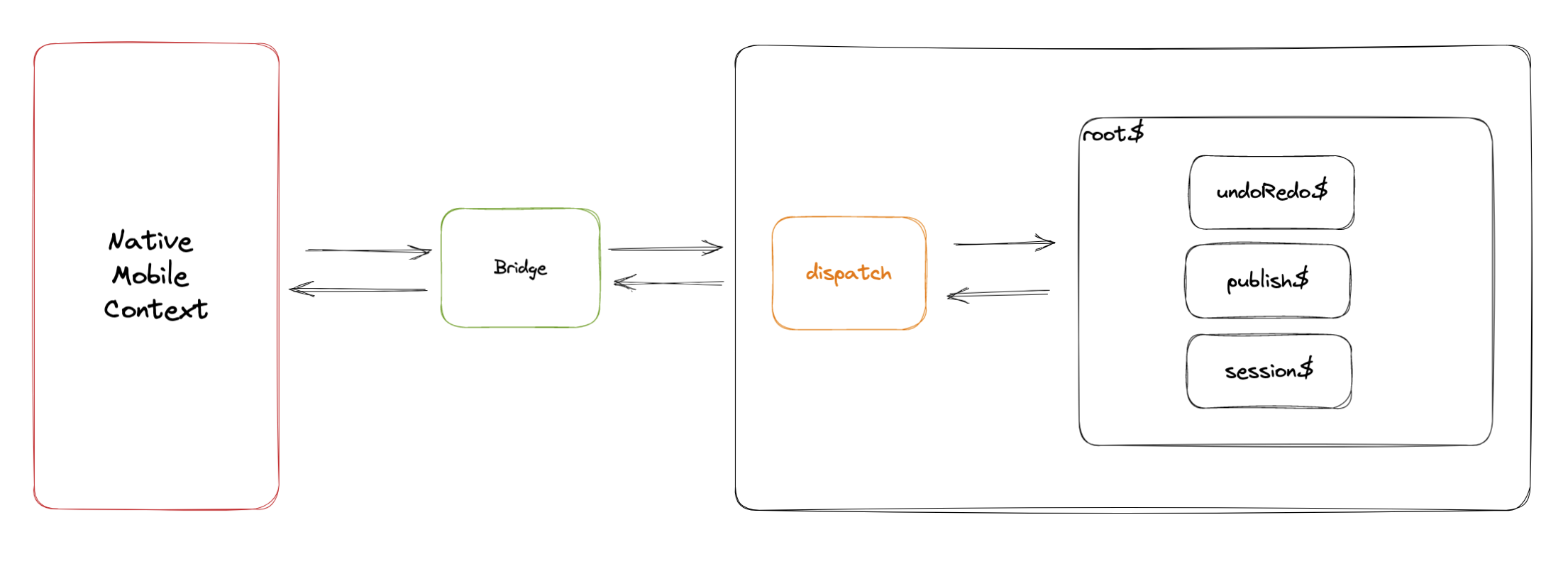

Ok, so that’s pretty simple, right? We create an RXJS Subject called $state. Every time an action is dispatched through our middleware, we publish the message to the Subject. Our $root observable also returns actions that the middleware dispatches. This works similarly to redux-observable by creating a loop of actions. But what is root$ in this code? It’s our main observable where we add all our concerns. We wanted this middleware to be as simple as possible and we haven’t touched it since it was first built.

To give you an idea of how simple the root$ observable logic is, have a look:

import { merge, Observable } from 'rxjs'

import { Action, State } from '../../types'

import loadSession$ from './loadSession$'

import publish$ from './publish$'

import saveSession$ from './saveSession$'

import undoRedo$ from './undoRedo$'

export default function root$(state$: Observable<{ state: State; action: Action }>) {

const observables: Observable<Action>[] = [

publish$(state$),

loadSession$(state$),

saveSession$(state$),

undoRedo$(state$),

]

return merge(...observables)

}

As you can see, we import our observables that address specific use cases. We merge them and their output is dispatched again as actions. Here’s a diagram of how it all fits together:

It’s interesting to note that we don’t automatically pipe every action inside our React app to the native context because we found it lead to degraded performance due to the cost of serialization. We ended up with a little utility function that we use to selectively pipe actions to the native context:

export function shouldSendActionToNative(action: Action): action is BridgeAction {

const actionTypes: ActionType[] = [

'initialized',

'publishSiteError',

'undoRedoApplied',

...

]

}

Summary

In this post, you learned how we take bridge messages and treat them as actions. We pump these actions to observables where we can deal with them in a resilient way. This is a very powerful pattern that we’ve been using in our app for a while now. This approach helps us a lot to deal with issues that we experience with in our app. A few examples are: rapid-fire messages, retries, error handling, and more.

The post doesn’t go into the specifics of bridging because you can find a lot of information about that online. Hopefully you find this approach to bridging actions coupled with RxJS observables useful and can apply it to your own projects.

Cover Photo Attribution: Photo by Modestas Urbonas on Unsplash